E.B. Bartels Wrote the Book on Pet Grief

The author’s new book explores different cultural rituals for memorializing a pet — from tattoos to taxidermy.

share article

Your pet wants you to read our newsletter. (Then give them a treat.)

When E.B. Bartels’ childhood pets died, she didn’t have a guide for grieving. Instead, feeling alone, she would hide her emotions from classmates who she worried would judge her for mourning an animal. “I felt very alone in those feelings,” Bartels says. “I think I often felt, especially when I was a kid, like such a weirdo for being as sad as I was when my pets died.”

Years later, in her MFA program, Bartel started writing about pets as a way to distract herself from the less cheerful subjects of her thesis. She brought one of these pieces into class, and the response blew her away. People related to the depths of her feelings, and they were eager to share their own stories. When a friend recommended that Bartels researched the pet grieving practices of different cultures, Bartels went down a rabbit hole — and her new book, Good Grief: On Loving Pets, Here and Hereafter, was born. Good Grief is made up of personal memories, academic research, and firsthand interviews, all on worldwide rituals surrounding pet death. The Wildest talked to Bartels about the process of assembling her novel and how the book changed how she understands grief.

Tell me about your pets!

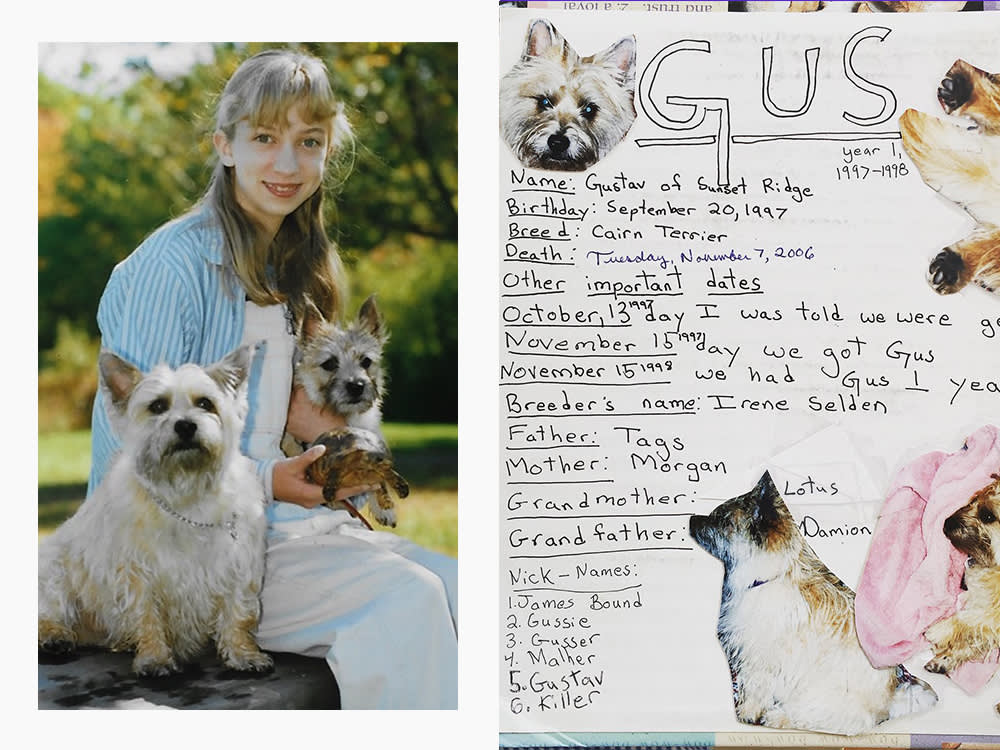

I grew up with lots of pets. I was an only child, sort of; I have three half siblings who are 10 to 15 years older than I am, so I was by myself a lot, and I turned to my pets for companionship. Growing up I had fish, I had birds, I had turtles and a tortoise and then I eventually had dogs.

What about now?

As an adult, I adopted a tortoise; his name is Terrence. He has his own instagram, which is @theofficialMr.Topens in a new tab — I haven’t gotten sued yet. I guess Mr. T’s not very active on social.

I have Seymour who’s a dog; we did the DNA testopens in a new tab, and he’s mostly Chihuahua and Pit Bull, and then also, like, 20 different types of Terrier. He’s tiny and super prey-driven. We also have two fancy pigeons who we rescued. My husband has always loved pigeons and we saw them one day on Petfinder. We were like, we have room to build a loft and give them space in our house now. We also have a fish tank, which really is Richie’s arena. I don’t want to mess up the water and accidentally kill them all. He keeps African Cichlids. We have, currently, 13 of them.

What motivated you to write this book?

The short answer is that I’ve had a lot of pets, and if you have pets you know that they always die in the end. Well, I joke that Terrence is going to outlive all of us. The dog barks at him and he just looks at him like, “I’m gonna live longer than you, buddy.”

But animals always brought me so much joy and happiness and comfort that I’ve always returned to getting pets over and over, even if their deaths were really sad and hard. When I had to euthanize our dog, Gus, when I was 18, that was the first time I had to do something like that, and it was awful. But then what did I do first thing during COVIDopens in a new tab? Get a dog.

When did you start compiling stories?

Ten years ago I started my MFA program at Columbia. My thesis was about something else entirely. When I needed a break from working on that material, I’d find myself writing about other stuff that always turned out to be about pets. I brought in some of these pet essays to some of my workshops and my friends in the workshop really responded to the material. They started telling me how they’d buried their animals and all the different things their families had done.

My friend Laura, who has a reporting background, she said, “You know, it’d be great if you did some research on how different cultures or different families or communities or religions have honored pets in the past.” She made the point that there’s no one real consistent thing that everyone does.

What was it like beginning the research process?

I thought, “Sure, I’ll do some research and sprinkle in a few fun facts.” I started looking into it, and there was so much out there. I was just surprised. I didn’t know about a lot of these rituals and practices, and I feel like I’m someone who has always been immersed in the pet world. I like to say I think my book is sort of an encyclopedia of options for once your pet dies — different things to think about. I’ve kind of wished that I’d had something like that.

There are amazing academic texts about pet-grieving rituals. I wanted to try to pull these different pieces into one book as a sampling of the rituals that are out there so that when your pet does die, and you’re overwhelmed and don’t know what direction to go in, you can see some things to think about.

What are some of those rituals?

One of the ones I was most excited to learn more about was taxidermy. I’d always been intrigued by it, but I didn’t understand why someone would do it. I think a little judgmental part of me was like, “Oh, can people not let go and process that their pet has died, so they have to hang on to the corpse?” I spoke to people who had actually preserved their pets and I realized how wrong that assumption was.

A woman I interviewed who had her Boston Terrier preserved is more in touch with death than anybody else I’ve talked to. She’s a mortician and works at a funeral home. She sees taxidermy as creating a new work of art that takes the shell that housed her friend’s soul and makes a sort of sculpture out of it. To her it’s almost like a 3D photograph. I hadn’t really thought about it that way. I’ve been thinking about, when Terrence dies, maybe preserving his shell. But again, he’s going to outlive me.

Were there any places where rituals for pet grieving were standardized, or did you find that it always varies from person to person?

I had a hard time finding one in contemporary times that was standard. I think part of it comes from the fact that there’s such a big split in terms of how different religions think about animals in terms of if they have souls or not.

So many people I interviewed for this book talked about how even within a family, sometimes it was really hard. One parent wanted to do one thing, another wanted something else, the kids wanted to do something else entirely. Do we cremate the dog, do we bury the dog, do we leave the body at the vet? People ask me a lot, “When should I read this book? Should I read it right after my pet dies or right before?”

I’ve been joking that people should get it as soon as they get a puppy or a kitten. You should start thinking about this stuff so you have an idea of what to do so when your animal dies and you’re grieving and upset; it helps. It feels morbid, but it’s similar with people — write a will, think about funeral expenses.

What was the process of reaching out to people like?

I tried to be passive in how I found people. I wanted people to approach me because they wanted to talk about it; I didn’t want to force anyone to talk about something they had a hard time dealing with. I would post things on my Facebook page or Twitter saying things like “I’m writing about memorial tattoos; if you know anyone who’d be interested in talking to me, let me know.”

I also found that when I did find people to talk to, I made a point to always share my own stories too, which I know is not a traditional journalistic approach. But I found that people would open up a lot more quickly when I was open about sharing things like, “I missed a week of college when I lost Gus because I was so upset.”

Do you have any favorite interview moments?

There are so many. One person I think about a lot is a gentleman named Larry. His wife used to work at the same school where I used to go. She put me in touch with Larry because they had a Yorkie for many years. They loved this dog so much, and when he died, Larry wrote a poem in the dog’s honor and Joyce is Jewish so they basically sat shiva for the Yorkie. Then they buried the dog in a pet cemetery.

I think about Larry and Joyce a lot because they had another Yorkie then, and less than a year after I spoke to Larry he passed away. I remember talking to Joyce after Larry died and asked how the dog was taking it, and she said Larry left very specific instructions saying he wanted to make sure the dog knew that he was dead and not just MIA. Joyce and Larry’s son actually brought the dog to the funeral home so the dog could view his body. Most of what my book is about is people dealing with pet deaths, but pets have to deal with people’s deaths a lot. I would never want my animal to think I’d abandoned them.

What do you hope people take away from the book?

I think two things. One is I think I often felt, especially when I was a kid, like such a weirdo for being as sad as I was when my pets died. I felt very alone in those feelings. I remember especially in middle school and high school, being afraid to voice that I felt so upset about, you know, my parakeet dying. What I want people to take away is seeing all these stories — my stories, all the people I interviewed, all the vets I interviewed — and knowing you’re not alone. And there’s no right or wrong way to grieve. If you’re not hurting yourself and you’re not hurting anybody else, I really say do what you need to do. Whatever it is, do what you need to do.

How did writing it change how you feel about pet death?

I’ve learned there’s no right or wrong way to grieve. I think I felt for a long time that you had to follow certain rules and that’s really not the case at all. Every death is different, I guess. For each animal, for each person. Figuring out how to honor and appreciate that animal’s death is different, too. And writing this book has made me really appreciate the time I have with my pets.

You can see E.B. Bartels discuss Good Grief at McNally Jacksonopens in a new tab in New York City tonight, November 3rd, at 7pm.

Sio Hornbuckle

Sio Hornbuckle is a writer living in New York City with their cat, Toni Collette.

Related articles

![A dog resting its face on a wooden table.]() opens in a new tab

opens in a new tabDo Dogs Grieve When Other Dogs Die?

A study confirms our pets can have heartbreaking reactions to the loss of a canine companion.

![Man hugs his dog to his face]() opens in a new tab

opens in a new tabHow Will I Know When It’s Time?

End-of-life veterinary specialist Dr. Shea Cox on how to make the most difficult decision in your pet parenting journey.

![Portrait Of Large, Senior, Mixed Breed Dog On Beach]() opens in a new tab

opens in a new tab10 Tips for Grieving a Pet

For National Pet Memorial Day — Sept. 12th — we asked 5 grief experts how to cope with feelings of guilt after we lose a pet.

![A woman sitting on a couch with three dogs.]() opens in a new tab

opens in a new tabVictoria Lily Shaffer Wrote the Book on Dog Rescue

How the author and founder of Pup Culture Rescue is fusing her experience in the entertainment industry with her passion for animal advocacy.